The Garden State has quietly enacted a law that could transform water infrastructure in America.

Signed during Governor Christie’s waning days in office, New Jersey’s 2017 Water Quality Accountability Act (WQAA) introduced a series regulations requiring local water utilities to develop asset management plans, report on infrastructure conditions, and reinvestment adequately in their systems. For outsiders to the water sector, the WQAA might seem like a set of narrow, technocratic rules. But it’s really much, much more—not because of the rules themselves, but because the data that the rules will generate can change the way that people think about the crucial but unseen systems that sustain American cities.

A renaissance artifact in a German village helps explain why.

Drinking water and credit claiming

While Governor Christie was signing the WQAA, my wife and I were sightseeing in Germany. There we visited Wertheim, a small town nestled on the banks of a river. Right in the village square stands the Engelsbrunnen, or “Angel’s Well.” The village has been there since the 8th century, but this well was constructed in 1574. The well’s construction transformed life in the village—before the well was built, villagers had to walk 100 yards down to the river to fetch water.

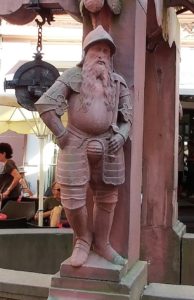

But the really interesting thing about this well is the structure that surrounds it. This wasn’t just a utilitarian bit of public works—it was, and remains, a jewel at the heart of the village. It’s named for the twin angel sculpture at the top of the structure, but what really stands out is the sculpture in front, at eye-level:

That is the mayor of Wertheim in 1574. He didn’t just want his people to have water, he wanted them to know who delivered it. And every day, when the villagers filled their pails of water, they’d do so standing face to face with the image of the mayor who built it. For Wertheim, the well was a major improvement in quality-of-life. For the Mayor, the Engelsbrunnen was what political scientists call a credit-claiming opportunity.

Politicians then, like politicians now, like to claim credit for good things. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, modern drinking water systems provided politicians with ample credit-claiming opportunities. And with good reason! Drinking water systems are amazing! They are the everyday miracles of the modern age.

Blame avoidance and infrastructure neglect

Unfortunately the politics of American drinking water have changed. For decades Americans have had the luxury of taking drinking water for granted. Maintaining or upgrading drinking water systems doesn’t offer the same kind of credit-claiming opportunity as building them.

When the public takes water for granted, leaders fear anger over rate increases, which they must balance against the fear of a disaster. As National Association of Water Companies CEO Rob Powelson put it: “No president or governor wants to have a Flint Water Crisis on their hands.”

That’s what political scientists call blame avoidance.

The thing is, blame-avoidance isn’t a very good motivator for infrastructure investment. If my political goal is to avoid blame for a disaster, then my tradeoff is tax or rate increases today vs. the risk of disaster on my watch. Rate increases today are immediately visible and unpopular; to politicians, the risk of disaster can feel remote—my successor’s problem, not mine.

From fear of failure to expectation of excellence

That’s where New Jersey’s WQAA has the chance to transform the politics of drinking water. With the data generated under this new law, researchers will be able to trace the full nexus of the relationships between costs, water quality, system performance, and capital reinvestment. We’ll be able to show how to maintain affordability while also maintaining public health and economic prosperity.

But most importantly, all that analysis can make water infrastructure a credit-claiming opportunity again. We’ll be able to quantify the health and environmental benefits that come from water infrastructure, and so give leaders a reason to brag about their investments in these critical systems.

My only gripe with the WQAA is its name: the word “accountability” implies a threat of punishment for failure, rather than opportunity for success. With due respect to the NJ legislature I’d have preferred a different name: the Water Quality Accountability Achievement Act. Water system maintenance, reinvestment, and public reporting on performance shouldn’t be feared as a cause of punishment, but embraced as a chance to celebrate excellence.

Hats off to New Jersey’s water leaders for seizing this moment and blazing a promising trail. New Jersey’s WQAA gives water sector leaders the chance to make this moment an inflection point: the time when water stopped being an afterthought and became a core policy concern again; when the water sector turned away from fear of failure and back to visionary achievement.