On the fiftieth anniversary of the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) in 2024, the Water & Health Advisory Council unveiled the Madison Declaration, which identifies five major drinking water challenges and five focus areas American drinking water policy over the next fifty years. Fellow WHACo Alan Roberson wrote about Enforcement in another post; in this one I take up another theme from the Madison Declaration: Justice.

TL:DR

The racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic correlates of drinking water contamination vary widely by contaminant. Advancing drinking water justice requires recognizing these differences in research and practice.

Justice is not a side issue or distraction for drinking water regulation; it is central to the SDWA's promise. Ten years ago, David Switzer and I began analyzing how Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) compliance intersects with race, ethnicity, and poverty. We found that health-related violations were more common in Black, Hispanic, and tribal communities—especially in rural and low-income areas. Experiencing these failures directly or observing them from afar, low-income and/or minority families often respond by buying costly, lightly regulated bottled water, deepening inequities and undermining democracy. Those findings helped change the national conversation over the past decade. American drinking water is now widely recognized as a leading environmental justice issue.

Pioneering researcher Robert Bullard called environmental justice the “the principle that all people and communities are entitled to equal protection of environmental and public health laws.” Ongoing, systematic social disparities in SDWA compliance demonstrate the environmental justice challenge facing the American water sector.

Some injustices develop because water systems lack the organizational capacity to operate effectively; some languish under irresponsible leadership. Regulators have been too tolerant of ongoing SDWA violations—often in systems serving smaller, poorer, and/or minority communities. The 2022 water crisis in Jackson, Mississippi stands as a signal example. For decades, Jackson’s municipal utility mismanaged and underinvested in its aging infrastructure, while state regulators and the U.S. EPA—fully aware of chronic violations—failed to enforce the SDWA with meaningful action. This long pattern of neglect, under Democratic and Republican administrations alike, culminated in a catastrophic system failure that left Mississippi’s majority-Black, low-income capital city without safe drinking water.

Jackson is now on the long road to recovery under the reorganized JXN Water, but that city’s experience shows how regulatory indifference and political abandonment can transform technical shortcomings into systemic injustice. Although Jackson is a particularly high-profile example, similar dynamics play out quietly each day in small systems that serve low-income and/or minority populations. Whether by strategic neglect or well intentioned tolerance of failure, the SDWA’s protections have not reached every community.

To eliminate social disparities and deliver on the promise of the SDWA, utilities must ensure that all of their customers enjoy equally great service. Regulators must no longer ignore or tolerate failure. Drinking water regulation must evolve to protect vulnerable populations as our society and economy evolve.

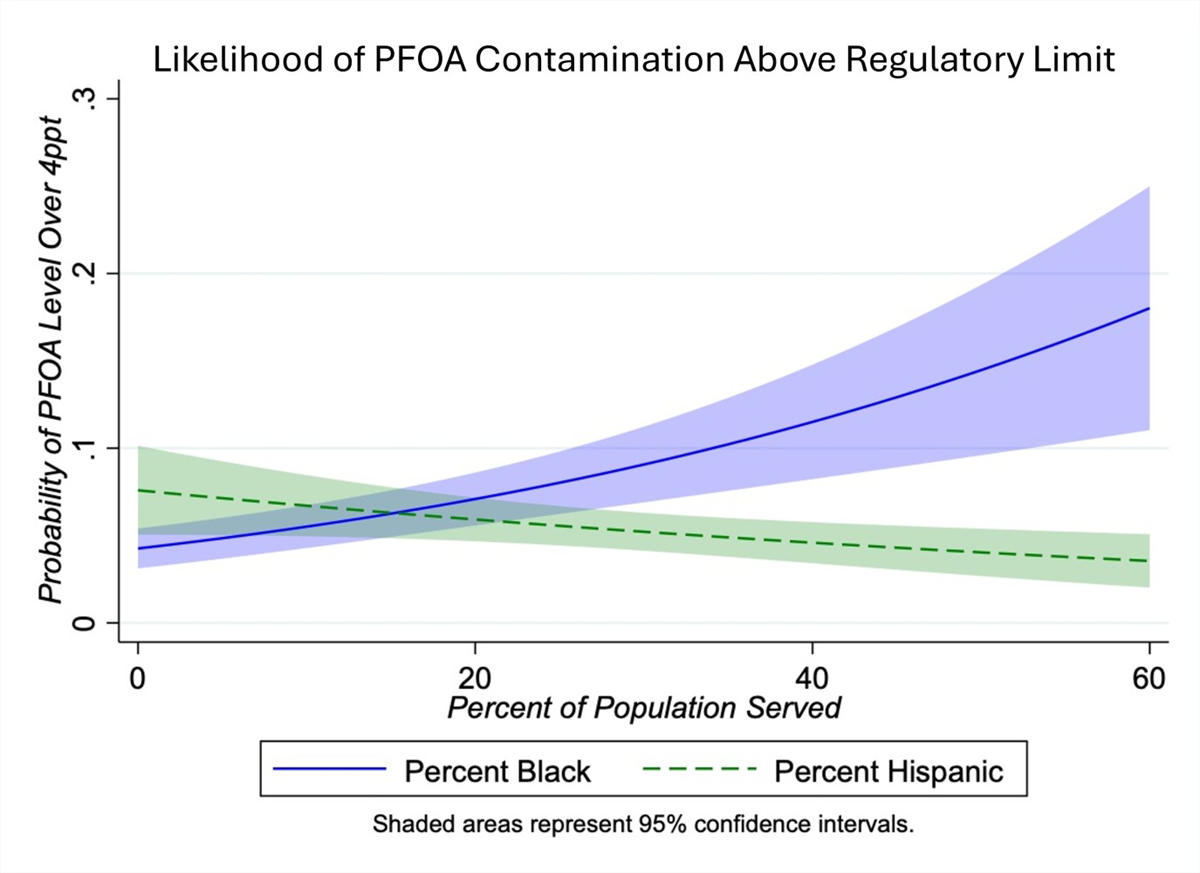

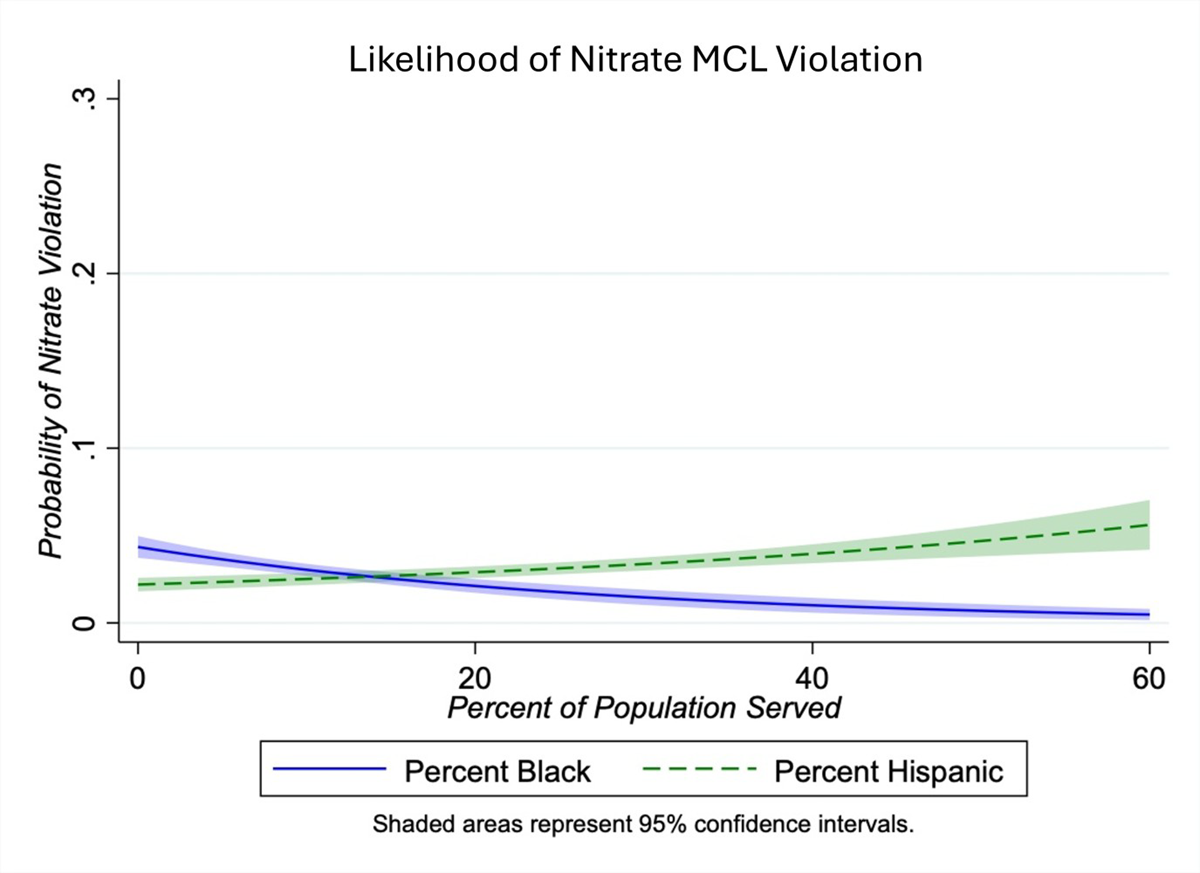

Here is where the justice conversation becomes more complicated, and more important, in the decades ahead. The most significant challenges for drinking water justice vary across the United States. In a recently published article and a forthcoming book, Michael Powell, David Switzer, Tess Teodoro, and I look at PFAS contamination like PFOA and PFOS alongside other contaminants. We find that the social correlates of serious drinking water contamination can vary markedly by contaminant — a result that complicates past environmental justice studies of drinking water (including my own!). Our analysis of EPA data shows that both income and percent Black population correlate positively with PFOA concentrations above the EPA’s new 4 parts per trillion (ppt) limit, but negatively with nitrate contamination above maximum contaminant limits (MCL). That is, the likelihood of PFOA contamination above the 4ppt limit is greater in higher-income communities and in communities with larger Black populations, but nitrate contamination is less likely in those same communities. Meanwhile, percent Hispanic population correlates negatively with PFOA contamination but positively with nitrate contamination.

Note: Estimates from logistic regression models, adjusting for water system size system age, source water, area median income, and income inequality.

The regulatory implications for environmental justice are profound: a disproportionate focus on PFAS contamination can unintentionally steer resources away from poor, rural communities to relatively wealthy, urban communities that likely have sufficient capacity to manage contamination. Since PFOA contamination is less likely but nitrate contamination is more likely in Hispanic communities, directing investment and regulatory attention to PFAS can effectively disadvantage an ethnic minority group that is more vulnerable to a less exotic contaminant. Future research on drinking water justice ought to evolve from analyses of compliance and violations to account for these nuanced, granular social differences across contaminants.

More importantly, the state agencies with primary SDWA implementation authority must maintain flexibility in setting enforcement and funding in ways that advance justice across this vast, diverse country. The SDWA’s 1970s-era regulatory model is in many ways too blunt an instrument for today’s complex environmental justice challenges. By treating all contaminants as equivalent, federal rulemaking ignores important distributional differences. Persistence, toxicity, and exposure pathways vary across contaminants and across social and economic contexts. Fortunately, under the SDWA, states can help achieve justice by directing investment and prioritizing enforcement toward the populations most at risk in ways that reflect local realities. In this way, regulators can respond more nimbly to emerging threats and make justice a core priority in drinking water policy.

The Madison Declaration calls us to imagine a future where every faucet delivers not only water, but justice, too. In Profits of Distrust, Samantha Zuhlke, David Switzer and I showed that unequal and unreliable tap water service erodes public trust, drives families toward costly bottled alternatives, and weakens the civic bonds that sustain democracy. When people cannot rely on their government to provide safe, affordable drinking water, they disengage from public institutions and retreat into commercial solutions that deepen inequality. When communities experience consistently safe, high-quality tap water, they are more likely to trust their neighbors, their utilities, and their governments.

Great drinking water is not just a matter of health—it is a foundation for civic life, democratic legitimacy, and the shared confidence that makes collective action possible. No branding campaign or clever communication strategy will (re)build trust at the tap unless and until water is safe and reliable everywhere and for everyone. Attaining that goal will be a generational project, but one that’s worth taking on. At a moment when trust in institutions is low and polarization is high, a commitment to healthy drinking water for every American holds out the promise of a healthier republic in the decades ahead.