You shouldn’t recruit survey participants through social media—or trust studies that do

Every couple of weeks a post hits my social media feeds asking me to participate in a survey somehow related to the water sector and suggesting that I repost it in hopes of recruiting more participants. These survey promotion posts come from consultancies, research firms, and sometimes even university researchers.

When I see these requests, I shake my head, mutter some uncharitable words, and scroll on. You should, too.

This is the second in an occasional series of posts about the virtues of careful sampling and the dangers of bad sampling in water management research.

Last time I wrote about the power of randomized, stratified sampling. This post takes up the perils of convenience sampling and the trouble with using social media to promote survey participation.

TL:DR

Using social media to recruit survey participants yields highly biased results. Don’t use social media to promote a survey, don’t participate in surveys promoted through social media, and don’t trust studies that use data from such surveys.

The easy path

Suppose that I’m tasked with assessing the quality of surface water in the United States. The U.S. is a big country with a lot of surface water—more than 3 million lakes, 250,000 rivers, and innumerable streams, swamps, brooks, bogs, and ditches. Gathering water samples from all of those bodies of water would be a herculean task requiring massive investments in labor and equipment!

Fortunately for me, there’s a nice pond just a quarter mile from my home, and Lake Mendota is only a half mile away! In fact, there are several more lakes within an easy 30-minute drive of my house! With just one day’s effort I could easily gather water samples from more than a hundred bodies of water in Dane County, Wisconsin—more than enough to calculate point estimates with confidence intervals and even fit fancy statistical models! Then I could publish my assessment of water quality in the United States. After all, my neighborhood pond, Lake Mendota, and Dane County are all in the United States!

Crazy, right? Waters that are conveniently located for Manny obviously don’t represent all the waters of the United States.

Thing is, every survey promoted through social media makes the same mistake—even surveys run by professionals and big-name institutions. These social media-driven samples aren’t representative, but they’re sure convenient.

The trouble with convenience sampling

Social scientists call this approach to data gathering “convenience sampling,” in which participants are selected based on their easy accessibility rather than through randomization designed to yield a representative sample. Researchers use convenience samples because they’re inexpensive, easy, and quick. While this approach can sometimes yield preliminary insights, their results are highly prone to bias and usually cannot really be generalized at all. In short, convenience sampling trades validity for expedience.

The classic illustration of convenience sampling cringe dates from the 1948 U.S. presidential election, when the Chicago Tribune famously ran the headline “Dewey Defeats Truman.” The Tribune based its predictions on telephone surveys drawn from automobile registration lists, which was an easy way to sample but disproportionately reached wealthier, urban, and Republican‑leaning voters.

That approach grossly undercounted lower‑income and rural voters who were more likely to support the Democrat, Truman. The result was a historic blunder. Sadly, it’s a blunder that remains all too common in water management research. Along with my own social media feed, I often see social media survey data show up in manuscripts submitted to AWWA Water Science.

LinkedIn vs. Randomized Sample

Surveys that rely on distribution through LinkedIn and other social media risk similar mistakes. To see what I mean, let’s look at water utility executives. Natalie Smith and I used randomized, stratified sampling to select a representative group of utilities.* We then actively gathered data about the leaders of those specific utilities. It was slow, painstaking work, but the result is a dataset that offers a high degree of confidence.

Instead of doing all that work, what if we had just posted a survey invitation on LinkedIn? That sure would be a lot easier. It would also yield very different results—and a very skewed picture.

As we were collecting other data, we also noted which CEOs had active accounts on LinkedIn,** which allows us now to compare the characteristics of the 41% of executives who are active on that social network with the 59% who are not. Let’s start with gender, race/ethnicity, and career path:Women make up a larger share CEOs are active on LinkedIn (15%) compared with those who are not (11%). Meanwhile, members of racial/ethnic minorities are a smaller share of LinkedIn active CEOs (12%) compared with non-LinkedIn active executives (14%). Executives who are active on LinkedIn are less likely to have been promoted from within (56%) compared with their peers who are not on LinkedIn (65%). Although these differences are notable, they aren’t statistically significant.

We start to see significant differences when we look at other aspects of executive backgrounds. For example, 60% of LinkedIn-active CEOs have private sector experience, compared to just 39% of CEOs who are not active on that social network. Educational credentials also diverge between the two groups.Most notably, much larger shares of CEOs who are active on LinkedIn have social science backgrounds (14%) and graduate degrees (57%) compared to their counterparts who are not active on LinkedIn (4% and 35%, respectively). MPA and MBA degree holders are more common among CEOs on LinkedIn, too.

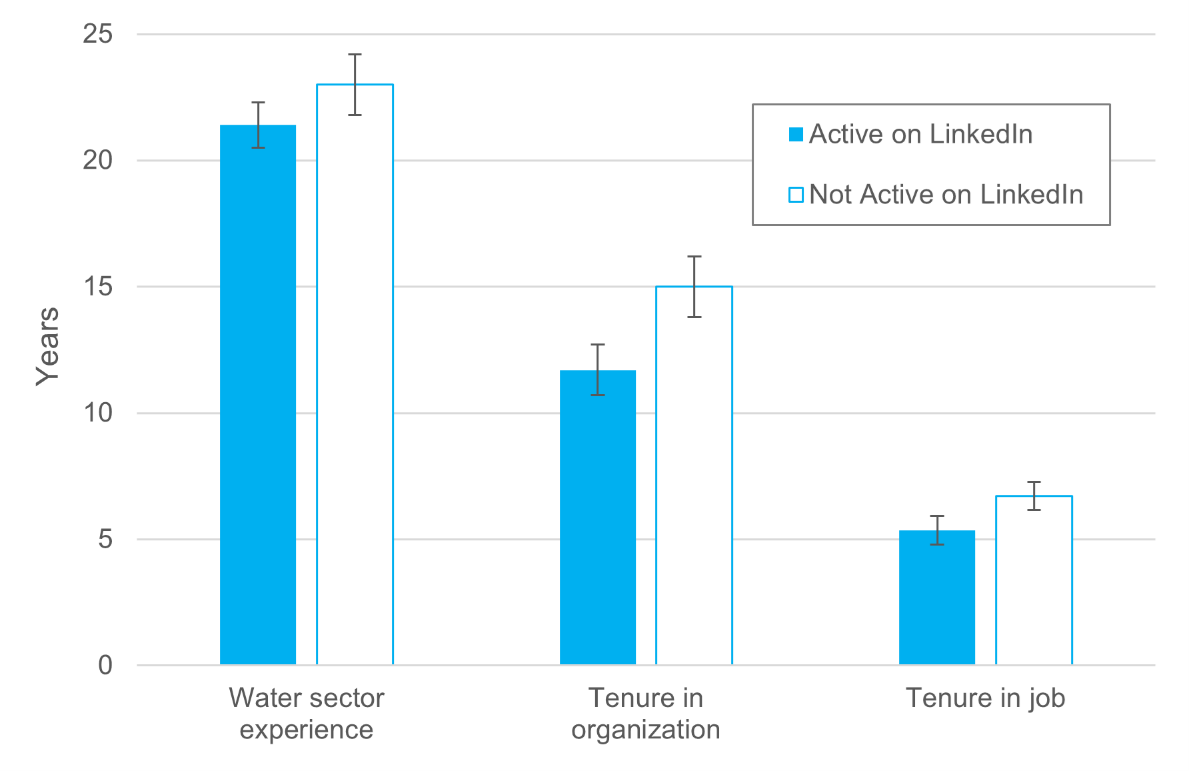

Experience and job tenure diverge markedly between the two groups, as well:

On average, leaders active on LinkedIn have 1.6 fewer years of water sector experience than CEOs who are not active on LinkedIn. The LinkedIn crowd also have an average of 3.3 fewer years in their organizations and 1.4 fewer years on the job.

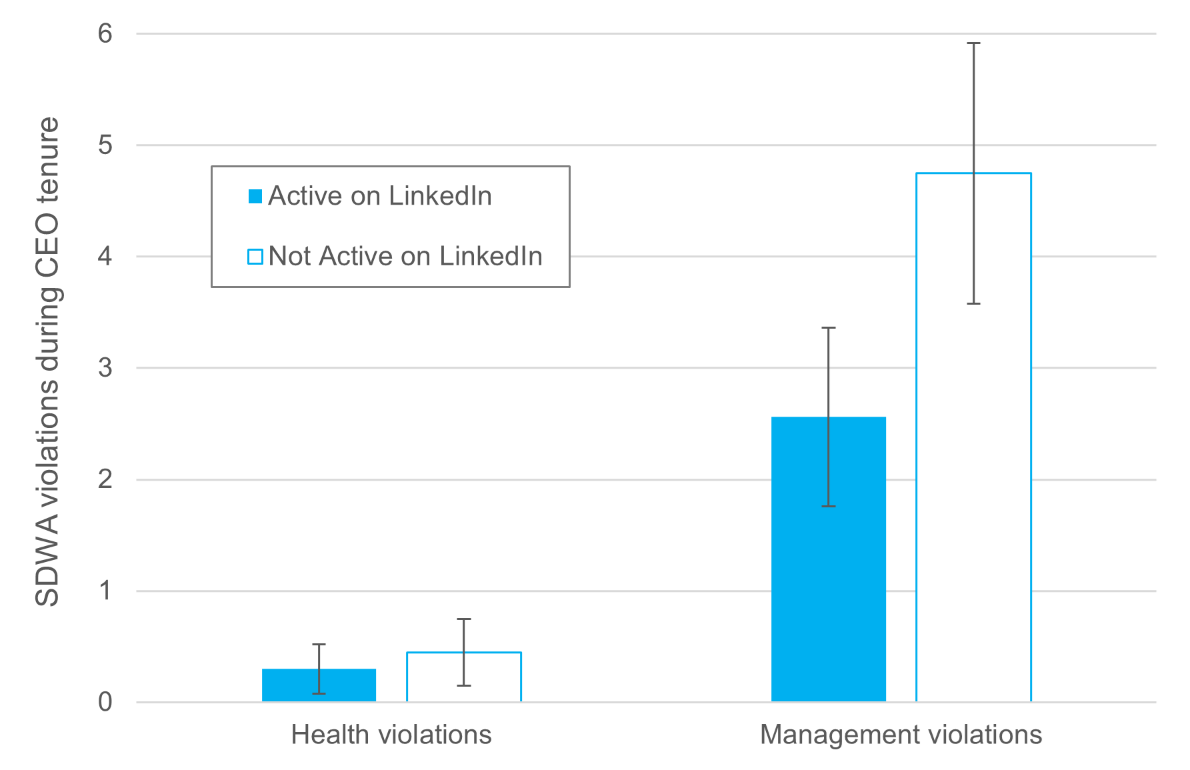

We also see a notable difference between LinkedIn and non-LinkedIn executives in Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) compliance:

There’s no significant difference in health-related SDWA violations by LinkedIn status, but utilities led by CEOs who are active on LinkedIn committed an average of 2.2 fewer management violations during their tenures compared with their peers who are not active on LinkedIn.

The bottom line is that any survey that uses social media to solicit responses is going to result in a biased dataset. In this example, a study of water executives that relied on LinkedIn would have concluded—incorrectly—that substantial majorities have private sector experience and graduate degrees. Now imagine what a social media sample would say about workforce development, cyberscurity, or communictions!

No shortcuts

Running surveys is deceptively easy in the internet age; anyone with Qualtrics and a social media account can bang one out, put it on blast, and start collecting data. That’s a recipe for rampant sample bias and an awful lot of bad surveys. Utilities and water sector organizations shouldn’t support surveys distributed via social media, water professionals shouldn’t participate in them, and nobody should take their results seriously.

Like good environmental research, good survey research requires careful sampling, thoughtful design, and the hard work of gathering valid data. That effort is worthwhile when critical infrastructure and basic services are at stake.

* My original 2012 study of CEOs used a very similar sampling method.

** LinkedIn accounts were coded as active if they posted, commented, or had been updated during the past 12 months.