The third pillar of affordability is Rate Design

This post is the third in a series outlining five pillars of affordability strategy for water and sewer utilities. None of these pillars is sufficient on its own, but together they offer a practical way to think about affordability comprehensively and strategically. Recent posts described the first two pillars of affordability: quality and efficiency.

Rate design is the third pillar of affordability. Careful rate design can help water and sewer utilities maintain affordability. A utility’s assets, liabilities, debt, and expenses—the stuff that shows up on a financial statement—contribute to the total or average costs to the utility of providing water services. But from a customer’s perspective, affordability depends on the prices that she has to pay for basic water and sewer service. Service prices can be higher or lower for the same volume of water, depending on the rate structures that utilities employ. In this way, rate structures can significantly affect the relative burden that utility service costs place on low-income customers.

Pricing the essential

Once utilities figure out how much revenue they need, they create pricing schemes designed to collect that revenue. We call those pricing schemes rate structures. Rate structures distribute a utility’s revenue requirements to different customers in different ways that can affect residential affordability. The vast majority of U.S. water utilities employ a combination of periodic fixed charges (e.g., $20 per month) and volumetric prices (e.g, $2.50 per thousand gallons). Although volumetric water pricing schemes come in a near-infinite variety, they typically fall into one of three basic types: uniform, declining block, and inclining block:

Uniform rates charge a single price for every unit of water consumed, regardless of total volume consumed. Declining block rates charge higher unit prices for low volumes of water, with unit lower per-unit prices at higher volumes. Inclining block rates charge lower unit prices at low volumes, with increased unit prices at higher volumes.

Residential water service is different from most other things that consumers buy because its use varies qualitatively by volume. Water can be used for essential needs like drinking, cooking, cleaning, and sanitation. Rich or poor, all of us need that basic volume of water—say, 30-50 gallons per person per day—to maintain good health. But water can also be used for discretionary needs, such as car washing and lawn irrigation.

Several empirical studies of residential water demand in the U.S. find a positive correlation between income and water demand linked to home size and discretionary outdoor irrigation.* In other words, water consumption for basic indoor use does not vary much by income, but discretionary use correlates positively with income. Since discretionary water consumption patterns correlate with income, rate structures can significantly affect the relative burden that utility service costs place on low-income customers.

Uniform and especially declining block rates are generally regressive insofar as they impose the highest prices on the most conservative customers and for the most essential volume of water, while charging lower prices for water associated with discretionary uses like lawn irrigation. Fixed sewer charges that apply the same prices to small, modest homes and large, sprawling homes are similarly regressive and bad for affordability.

Inclining block structures with low fixed charges, modest prices for low volumes, and steeply inclining prices at higher volumes bolster affordability by ensuring that essential indoor water use is available at relatively low total prices. Volumetric sewer prices and stormwater charges pegged to impervious surface areas are similarly good for affordability. Low fixed charges and inclined block rates allow customers greater control over their bill so price-conscious customers can adjust their water consumption to reduce their overall expenditures.

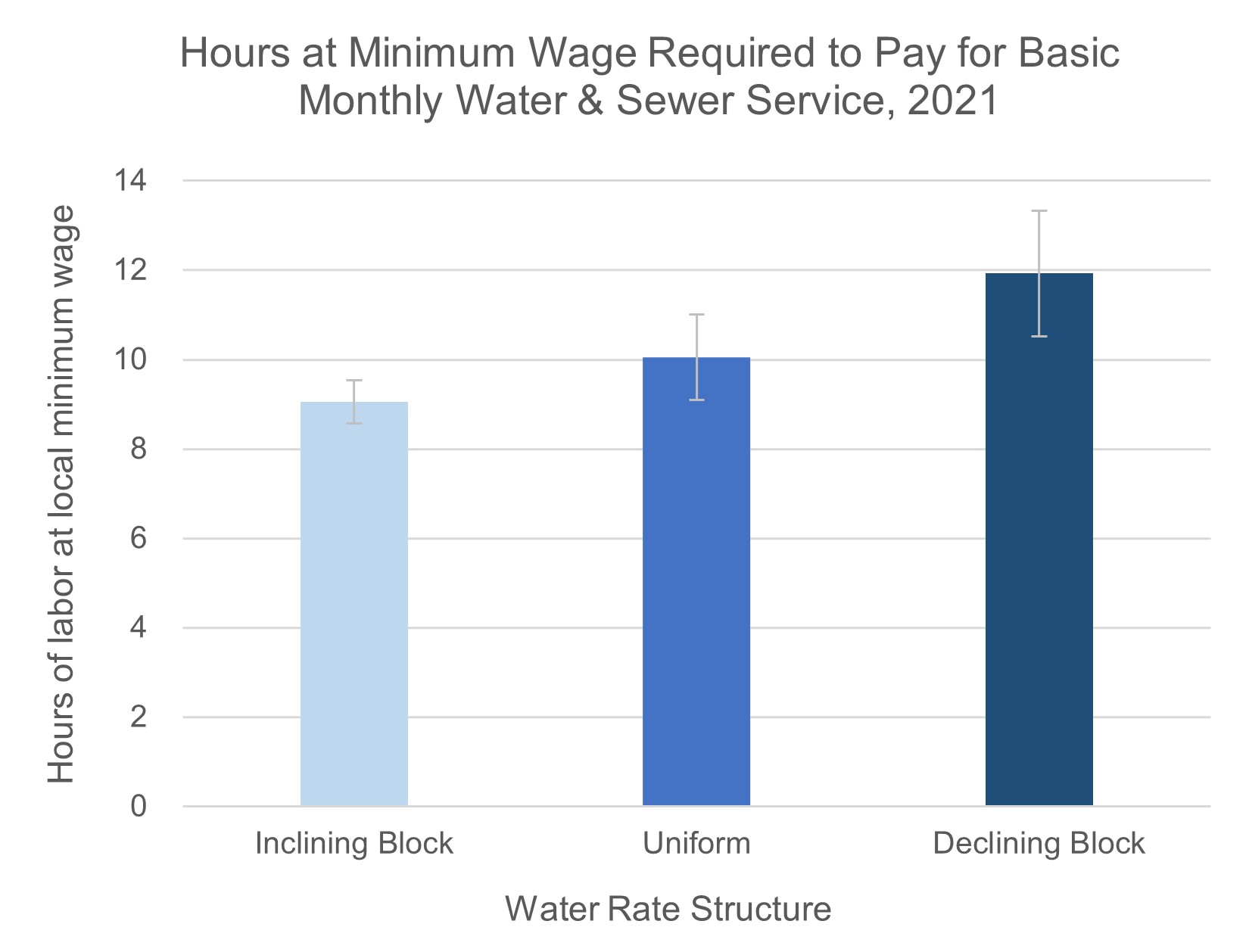

Nationally-representative water and sewer rates data from 2021 demonstrate the relationship between rate structure and affordability. Here are average hours at minimum wage required to pay for basic monthly service for a family of four (about 6,000 gal.) by water rate structure†:

Timing matters, too

Rate structures also vary in the frequency with which they bill customers: some utilities can send bills monthly, bimonthly, quarterly, semi-annually, or even annually. These differences can affect affordability. Low-income customers tend to have very limited savings and must manage household cash flows on a “paycheck-to-paycheck” basis. Empirical research demonstrates that low-income households can more easily manage smaller, more regular expenses than large, irregular expenses.**

Smaller, more frequent, and more predictable utility bills thus help maintain affordability. Monthly bills are preferable to bimonthly or less frequent bills from an affordability perspective—even if the total revenue collected from each customer is exactly the same.

Affordability without the administrative costs & burdens

Together, modest fixed charges, inclined block rates, low initial volume charges, and monthly billing represent a combination of best practices for water rate design aimed at affordability.

Crucially, these aspects of rate design provide affordability advantages to low-income customers without adding significant administrative costs to the utility and zero administrative burden for customers. Customers do not have to apply or qualify for special rates in order to benefit from a progressive rate structure and monthly billing. With affordability-friendly rate design, there’s no need for a working-class customer to apply for, appeal for, negotiate, or renew a benefit. Progressive rates don’t force utilities to add customer service or administrative staff to run assistance programs.

Like a vaccine that inoculates a population against a disease, good rate design automatically helps every residential customer with affordability. Progressive rate design won’t solve every low-income customer’s affordability problems—very large families in very old homes might use very high volumes, for example—so there is still a place for income-qualified assistance. But progressive rates translate efficient utility operations into affordable bills, and will help more people at far lower cost and with far less administrative burden than any income-qualified assistance program.

Affordability can remain a concern even when utilities provide high-quality service, operate efficiently, and price progressively. So long as these systems operate on a fee-for-service utility model, some people will still struggle to afford them. Responding to those financial struggles brings us to the fourth pillar of affordability: income-qualified assistance. I’ll take that one up next.

*See, for example, this study, this study, this study, and this study.

**See, for example, this study and this book.

†This relationship between rate structure and affordability persists in regression models that account for utility size, source water, and region.