Collecting tax revenue through water bills hurts affordability & turns utilities into coercive agents of government

They may not realize it, but tens of millions of Americans pay taxes on the water that flows from their taps and down their drains.

More than 38,000 general purpose governments (counties, cities, towns and villages) govern the United States. Each of those institutions requires revenue to function, and there’s an awful lot of variety to local public finance. Some local governments don’t tax utilities at all, and some impose taxes only on energy or telecommunications. But many local governments also tax water and sewer utilities—even when those utilities are owned and operated by the government itself.

These taxes take may forms. Some are clear to the customer; others lurk deep in the minutiae of city budgets. But wherever they exist and whatever form they take, water taxes make water less affordable and turn utilities into exceptionally regressive tax collectors.

Here are some of the common species of local water/sewer utility taxes that you might spot in the wild, arranged roughly from most overt to covert:

Miscellaneous city taxes & franchise fees

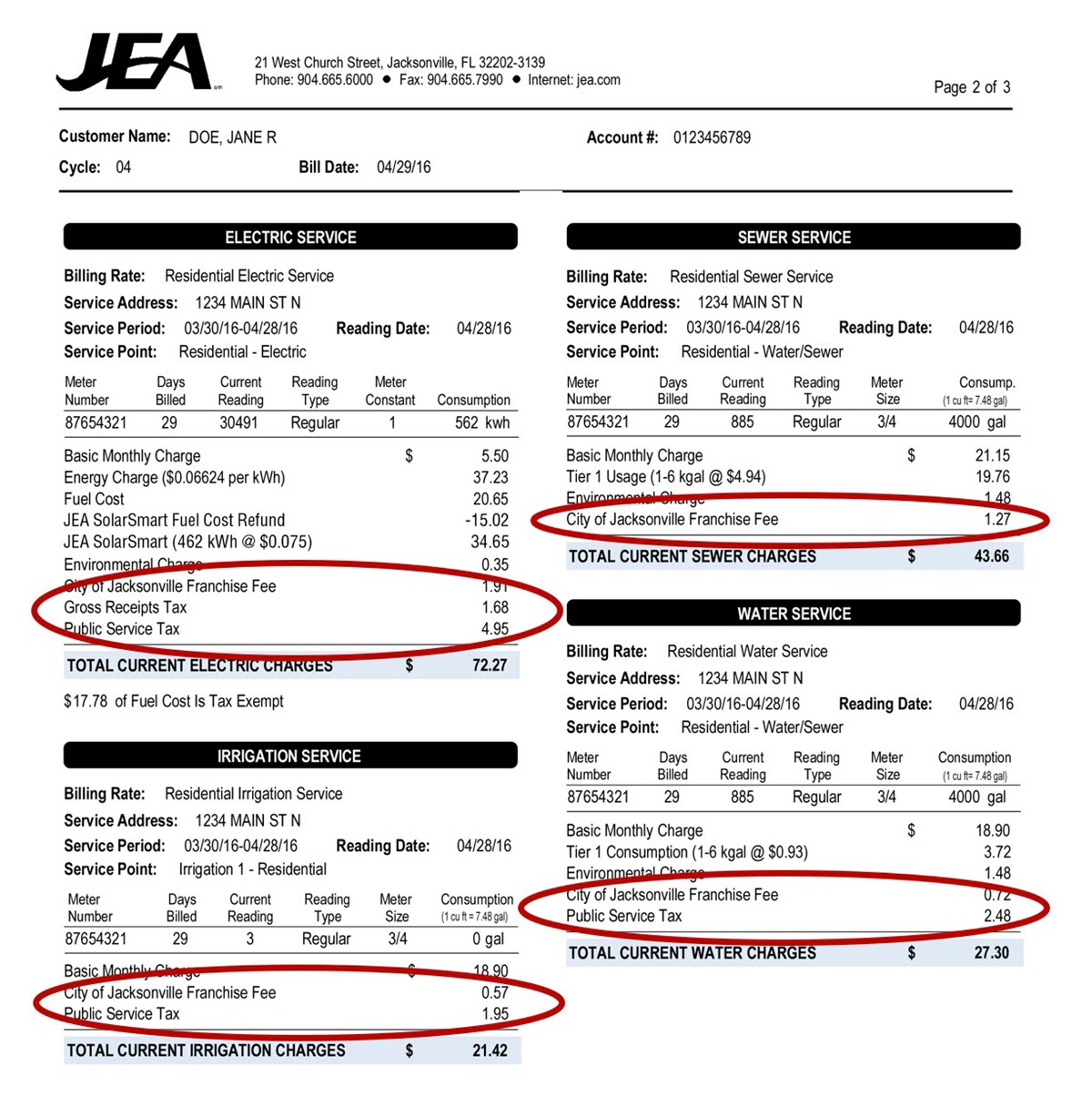

Many local governments tack minor taxes and fees onto water accounts, effectively turning their water utilities into tax collection agencies.

Phoenix is a great example. Water and sewer rates in the Arizona capital are relatively affordable, with monthly volume of 6 ccf costing only $48.83 even at the utility’s higher summer rates. But then local and state taxes mark up the charge 9%, the city adds a 70₵ stormwater tax, and the state adds a $1.00 monthly jail fee. On top of all that, the city adds another $1.50 “city services tax,” which Phoenix instituted in 2014 to close a city general budget deficit. Add it all up and the after-tax total is $56.43—up nearly 16%.

Another common practice is for cities to charge franchise fees to utilities, as in Jacksonville, FL. These fees are supposed to be something like rent on the utility’s use of public right-of-way, but that rationale is a little odd when the utility is a local government agency that the city created. Sometimes counties, cities, towns, and villages charge these fees to special districts that operate in their jurisdictions as a way to squeeze dollars out of another government.

Utility User Taxes (UUT)

In some places, customers pay taxes explicitly attached to utility service and calculated as a percentage of the utility service charge. City governments apply these taxes to customers of investor-owned utilities, as in Alexandria, VA (served by American Water), who pass on the tax to their customers.

But just as often, city UUTs apply to utilities owned and operated by the cities themselves. This arrangement is especially common in California, where scores of local governments levy UUTs to both investor-owned and municipal utilities. In Palo Alto it is 5%; in Stockton and San Jose it’s 6%; in Santa Cruz it’s 8.5%; in Compton it’s 10%. These taxes are usually, but not always, identified as lines on customer bills.

Gross revenue taxes

Some cities charge their utilities a tax on gross utility revenue: some percentage of rate revenue is sent to the local government general fund in the form of a tax. That’s right—local governments collect taxes on the revenue that their own water and sewer systems collect from service rates. 248 Florida municipalities impose "Municipal Public Service Taxes", as state law allows local governments to tax utility revenue up to 10%. Washington State law caps energy and telecommunication taxes at 6%, but sets no limit on water/sewer taxes.

These "business and occupation" taxes can be remarkably high in Washington State. Spokane takes 20% of its city’s water and sewer revenue in taxes; in Bellevue it’s 10.4% for water and 5% for sewer. My hometown Seattle charges a 15.54% "business tax" tax on all water revenue and 12% on sewer revenue that Seattle Public Utilities collects. Seattle has some of the highest water rates among large U.S. cities, but it turns out that a big chunk of that money goes to support the city government at large.

These taxes are imposed on utilities, as opposed to utility customers. The distinction is functionally meaningless, since the utilities pass the taxes on to customers in the form of higher rates. But levying the tax against utility revenue is politically advantageous: a tax on utility service shows up as a line on a customer’s bill, but a tax on utility revenue is a line buried deep in a city budget spreadsheet.*

Property taxes

Private, investor-owned utilities (IOUs) must pay property taxes on their land and buildings. These taxes are part of an IOU’s cost of service, which they recover through higher service rates. Property taxes can make up a big part of the monthly bill in communities that get their water service from IOUs. For example, in New York American Water’s (NYAW) Nassau County service area, as much as 30-50% of the water rates that customers pay go to property taxes. Last year alone, NYAW paid $19.5 million in town and village taxes, and another $23.5 million in school taxes. A first step in providing relief to ratepayers would be “to reduce or eliminate local property taxes on water companies,” noted a recent study.**

Government facilities are exempt from local property taxes. So municipal and special district water customers don’t have to pay for property taxes through their utility bills, right?

P.I.L.O.T.

Not so fast, my friend. Although they are legally exempt from local property tax, many city and special district utilities give Payments In Lieu Of Taxes (PILOT) to city or county governments. As the name suggests, PILOTs are supposed to compensate local governments for the tax revenue that they would have collected on utility land if it were held privately. But in practical terms, PILOTs simply transfer utility rate money from one government account to another. In Pennsylvania, these PILOT payments are called PURTA, and transfer millions in utility revenue to local governments’ general funds each year. Here in Wisconsin, PILOT payments by water utilities account for about 15% of total water rate revenue. From 2010-2019, Wisconsin drinking water customers paid more than a billion dollars in PILOT to their local governments.

PILOTs are entirely invisible to water customers.

Why water taxes are bad

Local governments need revenue. Who cares if they collect that revenue through utility bills? It’s all coming from the same people, right? There are at least four big problems with using money from water bills to pay for jails, parks, libraries, and everything else governments do.

1 - Taxes make water and sewer service less affordable.

In some places, 10-50% of water/sewer revenue goes to general government taxes. At a moment when many Americans face serious affordability challenges, these taxes make a bad situation worse.

2 - Water/sewer taxes are profoundly regressive ways to raise revenue.

A water tax is effectively a head tax. Water and sanitation are services that everyone must have to live. Unlike income taxes, property taxes, or even retail sales taxes, water taxes extract similar revenue from rich and poor alike.† For affluent customers, $10 in monthly taxes and fees is annoying; the same $10 can force working-class customers into delinquency.

There is something morally abhorrent about taxing goods that people need to survive—that is why nearly every U.S. state exempts groceries and medicine from sales taxes, and medical expenses are tax deductible. Water and sewer services ought to be exempt from taxes for the same reason.

3 - Low visibility of water/sewer taxes undermines accountability.

Few people notice the taxes that appear on their water bills, and utility revenue taxes, property taxes, and PILOTs are virtually imperceptible to anyone who isn’t an expert on local public finance. Water taxes allow government leaders to avoid voting for much more visible (and politically toxic) property, income, or sales taxes. A government that levies taxes on revenue collected by its own enterprises is playing a shell game and hoping that its citizens don’t notice.

4 - Utilities shouldn’t be tax collectors.

Taxes on water make the threat of shutoff a part of government’s revenue collection regime. Due process protects homeowners who fall behind on property taxes, and civil procedures shield those who fail to pay income taxes. But when taxes apply to water bills, the government response to nonpayment is denial of a life-sustaining service. Taxes are not entirely to blame for shutoffs, of course; it is impossible to know how many customers slip into delinquency or suffer shutoffs due to the extra tax burdens attached to their water bills. But taxes make bills higher, and higher bills mean more risk of delinquency. Denying water to a family because of a failure to pay taxes is ethically indefensible. Making utility operators serve as coercive agents of government is similarly repugnant.

My next post will tackle the question of what to do about utility taxes.

*It is probably not a coincidence that these utility revenue taxes are widely used in Florida and Washington—two states without personal income taxes.

**Of course, removing a water utility from the tax rolls doesn’t change the cost of running schools or local governments. Residents will enjoy lower water bills, but will pay with higher taxes.

†These taxes are most regressive under flat or declining block rates, which charge the highest prices to the most conservative customers.

There should not be a tax on your water and sewer bill. Water.is a product that a person needs to survive and should be considered food source. Where i live in a mobile home park they charge a service fee on both water and sewer one manreads it and they pay him 100 dollars but charge 16.33 service fee for the water and another service fee of 13.00 service fee for the sewer. Which is outrages.